New World vulture

| New World vultures | |

|---|---|

|

|

| American Black Vulture | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Superclass: | Tetrapoda |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Cathartidae Lafresnaye, 1839 |

| Genera | |

|

Coragyps |

|

|

|

| Approximate Cathartidae range map Yellow - Summer-only range of Turkey Vulture |

|

The New World vulture family Cathartidae contains seven species in five genera, all but one of which are monotypic. It includes five vultures and two condors found in warm and temperate areas of the Americas.

New World vultures are not closely genetically related to the superficially similar family of Old World vultures; similarities between the two groups are due to convergent evolution. Just how closely related they are is a matter of debate (see Taxonomy and nomenclature). They were widespread in both the Old World and North America, during the Neogene.

Vultures are scavenging birds, feeding mostly from carcasses of dead animals. New World vultures have a good sense of smell, but Old World vultures find carcasses exclusively by sight. A particular characteristic of many vultures is a bald head, devoid of feathers.

Contents |

Taxonomy and nomenclature

The New World vultures comprise seven species in five genera. The genera are Coragyps, Cathartes, Gymnogyps, Sarcoramphus, and Vultur. Of these, only Cathartes is not monotypic.[1] The family's scientific name, Cathartidae, comes from cathartes, Greek for "purifier".[2] Although New World vultures have many resemblances to Old World vultures they are not very closely related. Rather, they resemble Old World vultures because of convergent evolution.[3]

New World vultures were traditionally placed in a family of their own in the Falconiformes.[4] However, in the late 20th century some ornithologists argued that they are more closely related to storks on the basis of karyotype,[5] morphological,[6] and behavioral[7] data. Thus some authorities place them in the Ciconiiformes with the storks and herons; Sibley and Monroe (1990) even considered them a subfamily of the stork family. This has been criticized as an oversimplification,[8][9] and an early DNA sequence study[10] was based on erroneous data and subsequently retracted.[11][12][13] Consequently, there is a recent trend to raise the New World vultures to the rank of an independent order Cathartiformes not closely associated with either birds of prey or storks or herons.[14] In 2007 the American Ornithologists' Union's North American checklist moved Cathartidae back into the lead position in Falconiformes, but with an asterisk that indicates it is a taxon "that is probably misplaced in the current phylogenetic listing but for which data indicating proper placement are not yet available".[15] The AOU's draft South American checklist places the Cathartidae in their own order, Cathartiformes.[16] However, recent DNA study on the evolutionary relationships between bird groups also suggests that they are related to the other birds of prey and should be part of a new order Accipitriformes instead.[17]

Extant species

- Genus Coragyps

- Black Vulture Coragyps atratus in South America and north to US

- Genus Cathartes

- Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura throughout the Americas to southern Canada

- Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus in South America and north to Mexico

- Greater Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes melambrotus in the Amazon Basin of tropical South America

- Genus Gymnogyps

- California Condor Gymnogyps californianus in California. Formerly widespread in the mountains of western North America.[18]

- Genus Vultur

- Andean Condor Vultur gryphus in the Andes[19]

- Genus Sarcorhamphus

- King Vulture Sarcoramphus papa from Southern Mexico to northern Argentina

Extinct species and fossils

A related extinct family were the Teratornithidae or Teratorns, essentially an exclusively (North) American counterpart to the New World vultures — the latter were, in prehistoric times, also present in Europe and possibly even evolved there. The Incredible Teratorn is sometimes called "Giant Condor" because it must have looked similar to the modern bird. They were, however, not very closely related but rather another example of convergent evolution, though the external similarity is less emphasized in recent times due to new information suggesting that the teratorns were more predatory than vultures.[20]

The fossil history of the Cathartidae is fairly extensive, but nonetheless confusing. Many taxa that may or may not have been New World vultures were considered to be early representatives of the family.[21] There is no unequivocal European record from the Neogene.

At any rate, the Cathartidae had a much higher diversity in the Plio-/Pleistocene, rivalling the current diversity of Old World vultures and their relatives in shapes, sizes, and ecological niches. Extinct genera are:

- Diatropornis Late Eocene/Early Oligocene -? Middle Oligocene of France[22]

- Phasmagyps Early Oligocene of WC North America[22]

- Cathartidae gen. et sp. indet. (Late Oligocene of Mongolia)[22]

- Brazlian Vulture Brasilogyps Late Oligocene - Early Miocene of Brazil[22]

- American Dwarf Vulture Hadrogyps Middle Miocene of SW North America[22]

- Cathartidae gen. et sp. indet. Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, USA[23]

- Miocene Vulture Pliogyps Late Miocene - Late Pliocene of S North America[22]

- Peruvian Vulture Perugyps Pisco Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of SC Peru[23]

- Argetinean Vulture Dryornis Early - Late? Pliocene of Argentina; may belong to modern genus Vultur[22]

- Cathartidae gen. et sp. indet. (Middle Pliocene of Argentina[23]

- South American Vulture Aizenogyps Late Pliocene of SE North America[22]

- Long-legged Vulture Breagyps Late Pleistocene of SW North America[22]

- Geronogyps Late Pleistocene of Argentina and Peru[22]

- Amazonian Vulture Wingegyps Late Pleistocene of Brazil [24]

- Cathartidae gen. et sp. indet. (Cuba)[25]

Description

These birds are generally large, ranging in length from the Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture at 56–61 centimeters (22–24 in) up to the California and Andean Condors, both of which can reach 120 centimeters (48 in) in length and weigh 12 or more kilograms (26 or more lb). Plumage is predominantly black or brown, and is sometimes marked with white. All species have featherless heads and necks.[26] In some, this skin is brightly colored, and in the King Vulture it is developed into colorful wattles and outgrowths.

All species have long, broad wings and a stiff tail, suitable for soaring.[27] They are the best adapted to soaring of all land birds.[28] The feet are clawed but weak and not adapted to grasping.[29] The front toes are long with small webs at their bases.[30] No New World vulture possesses a syrinx,[31] the vocal organ of birds, therefore the voice is limited to infrequent grunts and hisses.[32]

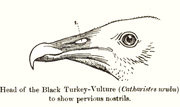

The beak is slightly hooked and is relatively weak when compared those of other birds of prey.[29] It is weak because it is adapted to tear the weak flesh of partially rotted carrion, rather than fresh meat.[28] The nostrils are oval and are set in a soft cere.[33] The nasal passage is not divided by a septum (they are "perforate"), so from the side one can see through the beak,[34] as in the Turkey Vulture. The eyes are prominent, and unlike those of eagles, hawks and falcons, they are not shaded by a bony brow bone.[33] Members of Coragyps and Cathartes have a single incomplete row of eyelashes on the upper lid and two rows on the lower lid, while Gymnogyps, Vultur, and Sarcoramphus lack eyelashes altogether.[35]

New World vultures have the unusual habit of urohidrosis, or defecating on their legs to cool them evaporatively. As this behavior is also present in storks, it is one of the arguments for a close relationship between the two groups.[4]

Distribution and habitat

New World vultures are restricted to the Western Hemisphere. They can be found from southern Canada to South America.[36] Most species are mainly resident, but the Turkey Vulture populations breeding in Canada and the northern US migrate south in the northern winter.[37] New World vultures inhabit a large variety of habitats and ecosystems, ranging from deserts to tropical rainforests and at heights of sea level to mountain ranges,[36] using their highly adapted sense of smell to locate carrion. These species of birds are also occasionally seen in human settlements, perhaps emerging to feed upon the food sources provided from roadkills.

Behaviour

Feeding

All living species of New World vultures and condors are scavengers. Though their diet is overwhelmingly composed of carrion, some species, such as the American Black Vulture, have been recorded as killing live prey. Other additions to the diet include fruit, eggs, and garbage. An unusual characteristic of the species in genus Cathartes is a highly developed sense of smell, which they use to find carrion. They locate carrion by detecting the scent of ethyl mercaptan, a gas produced by the bodies of decaying animals. The olfactory lobe of the brains in these species, which is responsible for processing smells, is particularly large compared to that of other animals.[38] Other species, such as the American Black Vulture and the King Vulture, have weak senses of smell and find food only by sight, sometimes by following Cathartes vultures and other scavengers.[31] The head and neck of New World Vultures are featherless as an adaptation for hygiene; this lack of feathers prevents bacteria from the carrion it eats from ruining its feathers and exposes the skin to the sterilizing effects of the sun.[39]

Breeding

New World vultures and condors do not build nests. Instead, they lay eggs on bare surfaces. One to three eggs are laid, depending on the species.[26] Chicks are naked at hatching and later grow down. The parents feed the young by regurgitation.[33] The young are altricial and fledge in 2 to 3 months.[32]

Status and conservation

The California Condor is critically endangered. It formerly ranged from Baja California to British Columbia, but by 1937 was restricted to California.[18] In 1987, all surviving birds were removed from the wild into a captive breeding program to ensure the species' survival.[18] In 2005, there were 127 Californian Condors in the wild. As of October 31, 2009 there are now 180 birds in the wild.[40] The Andean Condor is near threatened.[19] The American Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture, and Greater Yellow-headed Vulture are listed as species of Least Concern by the IUCN Red List. This means that populations appear to remain stable, and they have not reached the threshold of inclusion as a threatened species, which requires a decline of more than 30 percent in ten years or three generations.[41]

In culture

The American Black Vulture and the King Vulture appear in a variety of Maya hieroglyphs in Mayan codices. The King Vulture is one of the most common species of birds represented in the Mayan codices.[42] Its glyph is easily distinguishable by the knob on the bird’s beak and by the concentric circles that represent the bird’s eyes.[42] It is sometimes portrayed as a god with a human body and a bird head.[42] According to Mayan mythology, this god often carried messages between humans and the other gods. It is also used to represent Cozcaquauhtli, the thirteenth day of the month in the Mayan calendar.[42] In Mayan codices, the American Black Vulture is normally connected with death or shown as a bird of prey, and its glyph is often depicted attacking humans. This species lacks the religious connections that the King Vulture has. While some of the glyphs clearly show the American Black Vulture’s open nostril and hooked beak, some are assumed to be this species because they are vulture-like and painted black, but lack the King Vulture’s knob.[42]

Notes

- ↑ Myers (2008)

- ↑ Brookes (2006)

- ↑ Phillips (2000)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sibley and Ahlquist (1991)

- ↑ de Boer (1975)

- ↑ Ligon (1967)

- ↑ König (1982)

- ↑ Griffiths (1994)

- ↑ Fain & Houde (2004)

- ↑ Avise (1994)

- ↑ Brown (2009)

- ↑ Cracraft et al. (2004)

- ↑ Gibb et al. (2007)

- ↑ Ericson et al. (2006)

- ↑ American Ornithologists' Union (2009)

- ↑ Remsen et al. (2008)

- ↑ Hackett et al. (2008)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 BirdLife International (2009a)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 BirdLife International (2009)

- ↑ Campbell & Tonni 1983

- ↑ Mayr (2006)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 22.9 Emslie (1988)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Stucchi (2005)

- ↑ Alvarenga (2004).

- ↑ Suarez (2004)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Zim et al. (2001)

- ↑ Reed (1914)

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Ryser & Ryser (1985)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Krabbe (1990)

- ↑ Feduccia (1999)

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kemp and Newton (2003)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Howell and Webb (1995)

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Terres (1991)

- ↑ Allaby (1992)

- ↑ Fisher (1942)

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Harris (2009)

- ↑ Farmer (2008)

- ↑ Snyder (2006)

- ↑ Stone (1992)

- ↑ "San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: California Condor". The Zoological Society of San Diego's Center for Conservation and Research for Endangered Species. http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-condor.html. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2001)

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Tozzer (1910)

References

- Allaby, Michael (1992). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Zoology. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0192860933, p. 348

- Alvarenga, H. M F. & S. L. Olson. (2004). "A new genus of tiny condor from the Pleistocene of Brazil (Aves: Vulturidae)." Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 117(1) 1 9

- American Ornithologists' Union (2009) Check-list of North American Birds, Tinamiformes to Falconiformes 7th Edition. AOU. Retrieved 6 October 2009

- Avise, J. C.; Nelson, W. S. & Sibley, C. G. (1994) "DNA sequence support for a close phylogenetic relationship between some storks and New World vultures" Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91(11): 5173-5177. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.11.5173 (PDF). Erratum, PNAS 92(7); 3076 (1995). doi:10.1073/pnas.92.7.3076b

- BirdLife International(2004). 2001 Categories & Criteria (version 3.1). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- BirdLife International (2009). Vultur gryphus. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 6 October 2009.

- BirdLife International (2009a). Gymnogyps californianus. In: IUCN 2009a. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 6 October 2009.

- Brookes, Ian (editor-in-chief) (2006). The Chambers Dictionary, ninth edition. Edinburgh: Chambers. ISBN 0550101853. p. 238

- Brown J. W. & D. P. Mindell (2009) "Diurnal birds of prey (Falconiformes)" pp. 436–439 in Hedges S. B. and S. Kumar, Eds. (2009) The Timetree of Life Oxford University Press. ISBN 019953503

- de Boer, L. E. M.(1975) "Karyological heterogeneity in the Falconiformes (Aves)" Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 31(10): 1138-1139. doi:10.1007/BF02326755

- Campbell, Kenneth E. Jr. & Tonni, E. P. (1983): "Size and locomotion in teratorns" (PDF) Auk 100(2): 390-403

- Cracraft, J., F. K. Barker, M. Braun, J. Harshman, G. J. Dyke, J. Feinstein, S. Stanley, A. Cibois, P. Schikler, P. Beresford, J. García-Moreno, M. D. Sorenson, T. Yuri, and D. P. Mindell. (2004) "Phylogenetic relationships among modern birds (Neornithes): toward an avian tree of life." pp. 468–489 in Assembling the tree of life (J. Cracraft and M. J. Donoghue, eds.). Oxford University Press, New York.

- Emslie, Steven D. (1988) "An early condor-like vulture from North America" The Auk 105:3 529-535

- Ericson, Per G. P.; Anderson, Cajsa L.; Britton, Tom; Elżanowski, Andrzej; Johansson, Ulf S.; Kallersjö, Mari; Ohlson, Jan I.; Parsons, Thomas J.; Zuccon, Dario & Mayr, Gerald (2006): Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils. Biology Letters, in press. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523

- Farmer A, Francl, K (2008) Cathartes aura University of Michigan Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 8 October 2009

- Feduccia, J. Alan. (1999) The Origin and Evolution of Birds Yale University Press ISBN 0226056414 p. 300

- Fisher, Harvey I. (1942) "The Pterylosis of the Andean Condor" Condor 44(1): 30-32.

- Gibb, G. C., O. Kardailsky, R. T. Kimball, E. L. Braun, and D. Penny. 2007. Mitochondrial genomes and avian phylogeny: complex characters and resolvability without explosive radiations. Molecular Biology Evolution 24: 269–280.

- Harris, Tim (2009). Complete Birds Of The World. Washington D.C: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0403-6. p. 72

- Howell, Steve N.G., and Sophie Webb (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-854012-4, p. 174

- Kemp, Alan, and Ian Newton (2003): New World Vultures. In Christopher Perrins, ed., The Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-777-3. p. 146

- Krabbe, Niels & Fjeldså, Jon. 1990: Birds of the High Andes. Apollo Press ISBN 8788757161 p. 88

- Ligon, J. D. (1967): Relationships of the cathartid vultures. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 651: 1-26.

- Mayr, G. (2006). "A new raptorial bird from the Middle Eocene of Messel, Germany." Historical Biology 18(2): 95–102

- Myers, P., R. Espinosa, C. S. Parr, T. Jones, G. S. Hammond, and T. A. Dewey. (2008) Family Cathartidae University of Michigan Animal Diversity Web Retrieved 5 October 2009

- Phillips, Steven J, Comus, Patricia Wentworth (Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum) (2000) A natural history of the Sonoran Desert University of California Press ISBN 0520219805 p,377

- Reed, Chester Albert (1914): The bird book: illustrating in natural colors more than seven hundred North American birds, also several hundred photographs of their nests and eggs. University of Wisconsin. p. 198

- Remsen, J. V., Jr., C. D. Cadena, A. Jaramillo, M. Nores, J. F. Pacheco, M. B. Robbins, T. S. Schulenberg, F. G. Stiles, D. F. Stotz, and K. J. Zimmer. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithologists' Union.

- Ryser Fred A. & A. Ryser, Fred Jr. 1985: Birds of the Great Basin: A Natural History. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 087417080X p. 211

- Sibley, Charles G. and Burt L. Monroe (1990) Distribution and Taxonomy of the Birds of the World. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04969-2

- Sibley, Charles G., and Jon E. Ahlquist (1991) Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: A Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04085-7

- Snyder, Noel F. R. & Snyder, Helen (2006). Raptors of North America: Natural History and Conservation. Voyageur Press. ISBN 0760325820 p. 40

- Stone, Lynn M. (1992) Vultures Rourke Publishing Group ISBN 0865931933 p. 14

- (Spanish) Stucchi, Marcelo; Emslie Steven D. (2005) "Un Nuevo Cóndor (Ciconiiformes, Vulturidae) del Mioceno Tardío-Plioceno Temprano de la Formación Pisco, Perú." The Condor 107:(1) 107 113 doi:10.1650/7475

- Suarez, William (2004) "The identity of the fossil raptor of the genus Amplibuteo (Aves: Accipitridae) from the Quaternary of Cuba" Caribbean Journal of Science 40: (1) 120 125

- Terres, J. K. & National Audubon Society (1991). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. Reprint of 1980 edition. ISBN 0517032880 p 957

- Tozzer, Alfred Marston & Allen, Glover Morrill (1910). Animal Figures in the Maya Codices. Harvard University Plates 17 & 18

- Wink, M. (1995): Phylogeny of Old and New World vultures (Aves: Accipitridae and Cathartidae) inferred from nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung 50 (11-12): 868-882.

- Zim, Herbert Spencer; Robbins, Chandler S.; Bruun, Bertel (2001) Birds of North America: A Guide to Field Identification Golden Publishing. ISBN 1582380902

External links

- New World Vulture videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- New World Vulture sounds on xeno-canto.org

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||